|

So as we compile a closely focused set of plans focusing on the needs of local producers and mapping the opportunities for transformative land reform in Matzikama we must confront a challenging context and ask big questions of the process we are involved in.

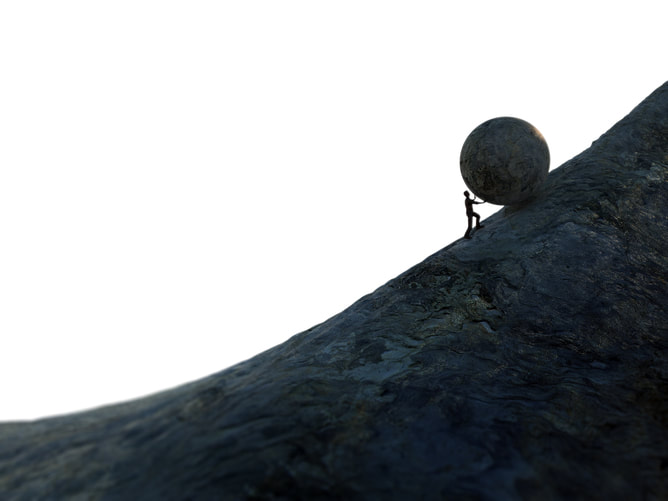

The first is a macroeconomic question. The budget for the Department of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development was reduced to 15.2 billion on 2020/21 in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Although the economy has shown signs of recovering faster than expected, government has expressed caution stating that it will "not commit to new long-term spending in response to temporary revenue windfalls". It was recently reported that the Treasury now sees the economic deficit at 7.8% of gross domestic product (GDP) this fiscal year, versus the 9.3% which was forecast in February. Treasury seeks to narrow this deficit to 4.9% of GDP in 2024/25. All of this means there currently is very little money available for land reform nationally and at local municipality scale state funding is negligible. So the question is how will this change? What will national, provincial and local government have to do to take advantage of the raising of the Clanwilliam dam wall and the availability of more irrigable land to promote employment intensive land reform? What fiscal flexibility does the Province have to prioritise and support significant land based opportunities? The second is an institutional question: What type of approach will best ensure decentralised planning and targeted support for land reform and land linked livelihoods, assuming that money and human resources will be allocated to this priority? President Cyril Ramaphosa stated In his 2021 State of the Nation Address that government would establish a land and agrarian reform agency to fast-track land reform during the course of the next financial year. The proposal for such an agency is not a new idea. Back in 2007 the Settlement and Implementation Support Strategy for Land and Agrarian Reform proposed that government choose between establishing a dedicated support directorate or a special purpose vehicle (SPV), with the day to day work being done by municipal level entities established as non profit companies. The SIS strategy also highlighted the importance of data and information management. It noted back then that: In the DLA there are more than 100 disconnected databases containing data relevant to different DLA functions and that there was no effective linkage between the data sets of different departments which deal with similar issues in similar areas of land reform. The strategy involved extensive engagement with a wide range of actors but despite being signed off by the then Minister SIS never went anywhere. It was closely followed by the Land and Agrarian Reform Project LARP in 2008 - an initiative of the Department of Agriculture. LARP stated with great confidence that: One of the most important lessons learned is the need for government to be more pro-active and integrated in its approach. Blazing a trail for the implementation of a more pro-active approach—known as Operation Gijima— LARP is based on a number of key principles to fast-track land and agrarian reform. It argued for "a well co-ordinated, aligned bottom-up approach based approach". Lessons may be 'learnt' but they seldom shape new direction. Unfortunately trail 'blazed' by LARP soon petered out, along with the undertaking to fast track land reform As the CBPEP thematic review of support services for smallholder and small-scale agricultural producers has analysed, LARP was "subsequently abandoned to be replaced by predominantly piecemeal interventions – each of which having relatively limited impact". The NDP was published in 2014 and proposed that each district municipality with commercial farming land in South Africa should convene a committee (the District Lands Committee) with all agricultural landowners in the district as well as key stakeholders. According to the NDP: This committee will be responsible for identifying 20 percent of the commercial agricultural land in the district and giving commercial farmers the option of assisting its transfer to black farmers. To date the NDP recommendations have not been implemented and there have been numerous questions about the status and value of plans developed with great fanfare and not insignificant expense which do not appear to practically guide the day to day work of the state. Next the Motlanthe High Level Panel took a close look at land reform and pointed to: A key gap in the legislative framework for land reform, and especially in relation to land redistribution, is the absence of an overarching framework law that guides and directs the ‘programme as a whole, as well as its various sub-’programmes. No such law exists at present. A key object of a framework law would be to clarify who the key beneficiaries of land reform should be, so that the goal of ensuring equitable access is achieved (p 220). The report proposed a new framework bill on land reform, to provides a coherent and consistent set of guiding principles; definitions of key terms such as ‘equitable access’; clear institutional arrangements (particularly at district level); requirements for transparency, reporting and accountability; and other measures that promote good governance of the land reform process. It even provided a draft of the legislation to get help get the process started. The recommendations of the HLP have not been implemented. The Final Report of the Expert Advisory Panel on Land Reform and Agriculture (2019) had more to say about support to land reform beneficiaries, noting that at the heart of the problem lies the poor state capability, which was characterised by ‘deficient coordination, limited and misaligned allocated resources (both public resources and private resources, particularly the finance sector), and further complicated by corruption’. It also highlighted the inefficiencies in the process of land acquisition and the systemic challenges faced post-transfer. In particular, the panel noted: There is no law that obliges the State to provide post-settlement support in redistribution and restitution projects. There is a lack of nationally-available information on production support provided in redistribution projects. There is evidence that many projects lack farming or production implements or even basic forms of support. The Advisory Panel identified the land reform budget, and post–settlement investment by key departments as being at the core of failure. It showed that the budget for the DRDLR has only been at maximum of 0.44% of the national expenditure, and in 2019/2020 was only 0.2% of the national expenditure. The panel pointed to ‘weak coordination between the DRDLR and the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF), and the provincial departments of agriculture, as well as misalignment of their mandates and budgets’. The panel proposed the establishment of a Land and Agrarian Reform agency – incorporating all the land reform functions of DRDLR and DAFF. It was proposed that these would include policy and planning, valuations, beneficiary selection, land identification and acquisition, implementation, post-settlement support, monitoring and evaluation. As recently as August 2021 Kirsten and Sihlobo argued that "the proposed agency could accelerate land reform by removing the process from political and bureaucratic control. The state’s only role would be to create an enabling environment. The heavy lifting would be the task of landowners, agribusinesses and large corporates". To date there is nothing publicly available to indicate the progress on the President's SONA undertaking to establish such an agency. There is no public clarity on what form it would take. or how its operations might be funded. So this context (briefly described above - there is much, much more) forms the backdrop to our work in Matzikama as we add another chapter to this long evolving story. In Matzikama we are pushing a familiar boulder up the hill once more. If finally we are to make it to the top, something fundamental has to change. A recent publication by Cormac Russell highlights the vital role of connectors and observes that "community building proceeds at the pace of trust". Our work process in Matzikama has emphasised the importance of the connector - the careful process of helping people out of their institutional safe havens to meaningfully engage with one another, to explore the possible. Throughout this process it is abundantly clear that without trust nothing can proceed. Every time there is a new initiative like this one there is a rekindling of dialogue and the re-emergence of hope which creates the possibilities for change. So soon we will be asking the question whether there is sufficient political will among the various national, provincial, district and local actors to remove the structural obstacles and help make meaningful change happen to enable us to get the boulder to the top of the hill. The alternative looks soberingly familiar.

0 Comments

|

Phuhlisani NPCPlanning Pilot facilitator Archives

June 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed